Table Of Contents

This site is pretty public.

It’s built with Astro and hosted on Cloudflare pages. It can get a ton of traffic when an article gets on the front page of Hacker News, so I need to make sure it’s reasonably small and usable with JavaScript disabled. I’m therefore not running my own server. Cloudflare builds my Astro site as static content and then hosts it on their CDN.

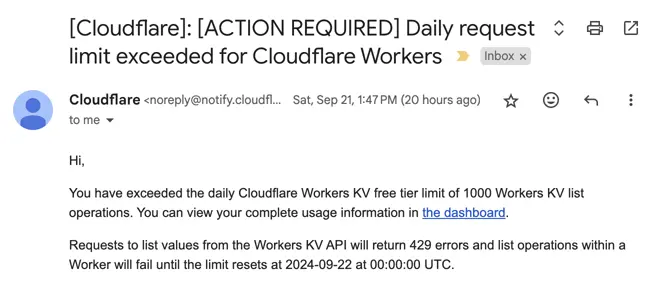

I have some other sites that make use tier-limited services. I usually don’t publicize them, so it was weird waking up to this email.

It’s particularly weird because Cloudflare is usually good about blocking bot traffic. Traffic spikes from them tend to mean real users. One of my non-public applications was getting real user traffic? I don’t mind paying if my site is getting organic traffic, but I’d like to know if that’s true first.

I googled - the only link I found was from an article I posted recently. Nothing else.

Cloudflare has its own analytics engine. The one you get from the free tier is pretty useless if you’re looking for more specific information. For $25/month I can get slightly better analytics on my personal project or I can rewrite my entire application and do the analytics myself.

#What I built

What was I even building that made use of Workers KV? A link shortener.

I had grand ideas for this. It’s something I might want to explore in the future, but I never got around to letting it support multiple users anyway. It’s just associating a shortened key with a URL value on a neat looking frontend with GitHub OAuth.

Cloudflare generously allows for 100,000 reads/day under its free tier, so why did the email say I hit the limit of 1,000? I was using a list operation to get all of the keys to display an overview of the links. Workers KV is likely more suited for storing large JSON files behind keys. There’s no reason why I couldn’t just use a single JSON record for all my site’s data.

Honestly, why am I even using Workers KV for this? JSON on a CDN is fine. I don’t need incredibly fast update times here.

Let’s rebuild this.

#The Rebuild

The simplest approach is a literal JSON value in GitHub with a frontend using document.location to redirect the user on page load. It’s a bit less clean than a Location header redirect since you need to download and parse the HTML first, but it would work.

However, I’ve recently got into markdown-based databases. I have markdown files syncing between my phone, laptop, and VPS. I can make edits on my phone and see them reflected on a live website pretty quickly. It’s both elegant and scrappy. It doesn’t scale, but it doesn’t need to. What if I use the same for my link shortener?

So I make a new file called Shortcuts.md. It’s a bulleted list with the name of the shortened link and then the link data on indented bullets.

- icons - https://www.xicons.org/- lofi - https://lofigenerator.com/- noise - https://asoftmurmur.com/You might think some other format would make more sense (e.g. name:link), but this is markdown. I can edit it on my phone and laptop pretty easily using markdown editing and viewing software. It would be annoying to edit YAML on a phone.

This application runs on Deno behind a Caddy reverse proxy. I’ve been building out my own logging and routing library on Deno for a while, but I need more robust analytics. I want to analyze this in a UI. I want tracing. I’m going to use OpenTelemetry.

#Using OpenTelemetry

JavaScript never seems to have any serious open source analytics infrastructure. There are paid services making libraries, but it’s hard to self host.

OpenTelemetry is relatively new software. It’s kind of like a logging output format with libraries for multiple languages. They call themselves an “observability framework and toolkit” if that helps somehow. By focusing on this niche, they can leave problems like storage and analysis up to other tools. It’s kind of cool, actually!

Annoyingly, the only OpenTelemetry server library that exists is for Node. They also expose a Web version. Really at its core, there’s not many parts of it that need to be Node-specific. Also luckily, Deno allows for node compatibility these days.

export function initializeOpenTelemetry(serviceName: string, version = '0.1.0') { const traceExporter = new ConsoleSpanExporter(); const sdk = new opentelemetry.NodeSDK({ resource: new Resource({ [ATTR_SERVICE_NAME]: serviceName, [ATTR_SERVICE_VERSION]: version, }), traceExporter, instrumentations: [getNodeAutoInstrumentations()], });

sdk.start();}This is all you need to initialize things. There’s a lot of “auto instrumentation” here. It monkey-patches a bunch of node modules to inject analytics. The traceExporter is the destination for where our logs go. In this case it’s just the console, but I’ll be changing it later to work with an actual observability UI.

initializeOpenTelemetry('redirects')const tracer = opentelemetry.trace.getTracer('requests');

const app = new Hono();

app.use("*", async (c: Context, next): Promise<void> => { const span = tracer.startSpan('handleRequest', { kind: SpanKind.SERVER, attributes: { method: c.req.method, path: c.req.path, userAgent: c.req.header("User-Agent"), // Cloudflare-specific header for getting the user IP ip: c.req.header("CF-Connecting-IP"), }, });

c.set('span', span)

await next();

span.end()});I moved over from my own router to Hono. It’s pretty neat and likely familiar if you’ve used express before. I’m creating “middleware” i.e. code that runs in between my router and my handlers. Here I’m creating a “span” which will allow me to attach information to a given request lifecycle. By doing c.set('span', span), I can pass the span object into the route handlers so we can continue passing data through the route.

As a quick aside, I wouldn’t need to pass anything explicitly if this were all synchronous code. We could get the last span “on the stack” and use that directly. Unfortunately, we can’t use the stack across asynchronous function calls in JavaScript. We’d need the yet-to-launch Async-Context for that. They even mention it!

In my handler itself, I pass around the span and add information to it.

app.get("/:link", async (c: Context, next) => { const span = c.get('span') as opentelemetry.Span

const links = await getLinks(span);

const path = c.req.path.slice(1); const link = links.publicLinks[path] ?? links.privateLinks[path];

if (link) { span.addEvent('got link', { url: link.url, description: link.description ?? '' }) return c.redirect(link.url); }

if (!path) { span.addEvent('sending public links') return c.json(links.publicLinks); }

await next();});With all that set up, what’s going on here?

#Analyzing the data

I’m using a self-hosted signoz instance to view my logs.

Most of the data comes in at night, but I still got some immediate traces coming in. Just looking at the paths being hit, we see a bunch of Wordpress admin and security routes.

/wp-admin/css/ 13.79.229.201/.well-known/radio.php 13.79.229.201/.well-known/acme-challenge/upfile.php 13.79.229.201/classwithtostring.php 13.79.229.201/wp-content/uploads/upload_handler.php 13.79.229.201/wp-includes/js/jquery/jquery.js 13.79.229.201/wp-includes//wp-includes/admin-bar.php 13.79.229.201/.well-known/pki-validation/index.php 13.79.229.201/wp-content/install.php 13.79.229.201/cgi-bin/xmrlpc.php 13.79.229.201Seems someone is phishing for vulnerabilities. It’s annoying that Cloudflare didn’t catch what looks obviously malicious, especially since there’s also no User-Agent header. While we’re no longer using CF Workers, I’m still using CF’s proxy on the DNS panel, so it should be doing similar request filtering.

Looks like more is coming in!

/.git/config 195.178.110.21 Mozilla/5.0 (Fedora; Linux i686; rv:122.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/122.0/wp-admin/css/ 157.173.114.2 Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/90.0.4430.85 Safari/537.36We’re seeing new IPs! Someone is throwing a botnet at me. Using an IP info lookup tool, these are coming from Azure, Contabo, GCP, Chinanet, Virtuo Host, Private Layer, Limenet, and many more!

13.79.229.201, 195.178.110.21, 157.173.112.0/20, 52.164.187.77, 194.38.20.13, 179.43.191.19, 91.92.242.175, 194.38.23.16, 43.153.93.68, 103.167.217.137, 85.209.176.21, 95.177.180.85, 192.36.109.98, 205.210.31.58, 167.249.140.45, 35.89.11.48, 114.80.36.40, 179.43.191.19Some interesting ones include a Tencent server in Santa Clara and some company named PPTechnology.

There’s nothing I can see in common with the addresses here. It looks like many distinct servers from different locations have all been exposed to some vulnerability and are now a part of a botnet.

#Blocking these requests

I want as much of this mitigation to be done from Cloudflare. It’s no help spending CPU cycles blocking requests when I could stop them a step earlier. Cloudlfare has a “Bot Fight Mode” which doesn’t seem to be very effective here. Luckily, they also have a security section where you can build custom rules.

I threw the IPs I listed above in a block list. The same IP isn’t used for more than a few requests and they’re not using the same provider, so I can’t just block IP ranges. This also means my block list caught 0 subsequent requests.

A majority of the requests were coming in without User-Agent headers or very specific ones. I added those to the block list. I want to accept browser requests, so I’m fine blocking anything clearly non-standard.

I could keep adding on strategies to ward off the botnet, but it’s not really a fight worth fighting. The requests don’t cost me anything and they keep scanning for PHP vulnerabilities on a site running with JavaScript.

At least now I know